Water Works

Hun Sen calls for immediate start to Funan Techo Canal, Cambodia launches $36.6 Billion building drive, Is Cambodia's Funan Techo Canal a Loss for Vietnam and a Win for China?

Hun Sen calls for immediate start to Funan Techo Canal

Senate president Hun Sen in a special video address to the nation at noon 16 May 2024.

Senate president Hun Sen has recommended that the government begin construction of the much-debated Funan Techo Canal as soon as possible.

“I would advise government leaders not to spend too long thinking about it. The project should start as soon as possible,” he said, in a special video address to the nation at noon today.

“I think the government should hold a groundbreaking ceremony,” he added.

The 180km canal project has received widespread support from the Cambodian people and may be started as soon as the end of the year, according to several government officials. It is estimated that the project will cost $1.7 billion, and take four years to complete.

Some commentators and critics of the government have linked it to alleged Chinese expansionism, with some even suggesting that it may have a military use (see below).

Hun Sen described linking the canal project to geopolitical issues as “ridiculous”. He said the width of the canal is very small, so vessel travelling on it would be an easy target for B40 rocket propelled grenades.

He explained that it was those who are against China that oppose the project.

“Security concerns for Vietnam make no sense at all, as China and Vietnam are friends and Cambodia and Vietnam are friends too. They won’t fight on Cambodian soil,” he said.

“Let me emphasise that there is no link to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. It is purely the initiative of Cambodia. It will support our socio-economic development and political independence through the Kingdom’s infrastructure,” he added.

“We must become independent in the transportation sector, and this goes beyond mere socio-economic development,” he continued.

He also pointed out that there is no requirement for Cambodia to negotiate with anyone, as the Kingdom follows article 5 of the 1995 Mekong Agreement, which specifies that only notification is needed for projects which are built on a tributary of the Mekong River.

He added that Cambodian had informed Vietnam and Laos of the project out of politeness.

Read more here.

Cambodia launches $36.6 Billion building drive

By Andrew Haffner (Aljazeera)

Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Manet has unveiled a 174-project master plan that has attracted bids by rival powers.

“It’s not even a competition, it’s like a pool of countries trying to be Cambodia’s best friend. Cambodia is open to whatever country that’s open to making Cambodia better – if they want to have their own competition of who can build the biggest bridge, go for it.”

US$36 Billion was the final sum calculated by the Cambodian government and published earlier this year in a 174-project master plan that would overhaul the national transportation and logistics network within an ambitious timeframe of just a decade. The goal to crisscross the kingdom with expressways, high-speed rail lines and other works fits closely with the state’s longstanding wish of becoming an upper-middle-income country in 2030 and a high-income nation by 2050.

Since the unopposed ascension last year of Prime Minister Hun Manet – the son of former Prime Minister Hun Sen, the country’s leader of nearly 40 years – his new government of aspiring technocrats has pressed forward with the building campaign, beseeching foreign allies for closer ties and increased investment while assuring the public of big things to come.

“We shall not withdraw from setting our targets in building road and bridge infrastructure,” Hun Manet said at a February groundbreaking for a Phnom Penh bridge funded with a Chinese loan.

“Roads are like blood vessels to feed the organs wherever it goes … soon we will have the ability not only to just possess [material things] but also for Cambodians to build by themselves infrastructural marvels such as bridges, highways and subways.”

Cambodia has experienced more than two decades of rapid economic growth with some of the worst infrastructure in Southeast Asia, according to the World Bank’s logistics performance index.

With the bank predicting accelerating gross domestic product (GDP) growth for the years ahead, Cambodia’s already stretched transportation system could be strained to breaking point.

While the new prime minister looks to cement his own status after his father’s long rule, making progress on hard infrastructure will present a test for his governance as well as the traditional Cambodian balancing act of international relations.

Rolling out the master plan with a to-do list of projects large and small could present an opportunity to benefit from geopolitical rivalries as foreign partners jostle for influence – especially as competition intensifies between two of its largest benefactors, China and Japan.

“I think Cambodia’s government feels it is high time to maximise whatever they can get from the donors,” Chhengpor Aun, a research fellow at Future Forum, a Cambodian public policy think tank, told Al Jazeera.

“It’s logical that if an infrastructure project initiated by the Cambodian government is not accepted by a partner, they could still go to the other partner to fund it. It’s strategic and flexible in the way they play the big powers against themselves to try to extract benefits.”

The Cambodian government and private businesses do fund infrastructure projects in the kingdom, but China and Japan together account for much of that investment.

Both are also the only countries to hold Cambodia’s highest diplomatic designation of “comprehensive strategic partnership”, a status Japan gained just last year.

So far, China’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has led the infrastructure charge with major projects such as the kingdom’s first expressway, which runs from the inland capital of Phnom Penh to the coastal city of Sihanoukville.

Meanwhile, Japan has kept its own steady agenda, focusing on a range of projects such as new wastewater treatment facilities and upgrades to existing roads.

Perhaps most notable is a Japanese-led expansion that could more than triple the capacity of the international deep sea port of Sihanoukville, the sole facility of its kind in Cambodia.

The bustling facility handles about 60 percent of the country’s import and export traffic and is increasingly congested after more than a decade of steady growth.

Under the oversight of the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), crews at the port broke ground on the expansion late last year.

The planned three-part, decade-long project is included in the new master plan and has a total estimated cost of about $750m.

“Compared with Chinese [infrastructure] investment, the amount of Japanese investment is very limited,” Ryuichi Shibasaki, an associate professor and researcher of global logistics at the University of Tokyo who has studied Cambodia’s shipping industry, told Al Jazeera.

“We need to find niche markets since there is so much investment from China, to fill the gaps or adjust investment to a more broad viewpoint.”

In recent years, the BRI has tightened its focus.

Accusations of China ensnaring poorer countries in “debt traps” have caused Beijing to turn away from issuing large loans to countries to fund megaprojects – typically defined as those worth more than $1bn – in favour of a more investment-oriented tilt towards projects with good expected returns.

These are typically funded with “build-operate-transfer” agreements, in which the company overseeing the work takes on the expense of developing it in return for the revenues generated by the finished project over a predetermined period.

At the end of the agreement, which can span decades, ownership transfers to the government of the host country.

Key pieces of Cambodia’s big-picture vision will depend on that kind of financing.

‘Trying to be Cambodia’s best friend’

The kingdom’s master plan for infrastructure includes proposals for nine megaprojects worth an estimated total of more than $19.1bn.

While most of these are still being studied for feasibility, almost all have been touched at some point by JICA or the China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC), a subsidiary of the state-owned giant China Communications Construction Company.

CRBC previously led the construction of Cambodia’s first expressway, which came online in late 2022 and has generally been hailed as a success.

The company broke ground last year on a second, $1.35bn expressway between Phnom Penh and Bavet, a city on the Vietnamese border, which is among the nine envisaged megaprojects.

It is joined by such works as another CRBC-studied expressway system that would link Phnom Penh to the major tourism hub of Siem Reap and the city of Poipet on the Thai border.

Split into two parts, construction of that road system is estimated at a total expense of $4bn. There is also an upgrade of one existing railway line to Poipet to accommodate high-speed trains for $1.93bn, plus another to Sihanoukville for $1.33bn.

The plan later calls for a light rail and subway system for the capital Phnom Penh and part of Siem Reap, all packaged together for an estimated $3.5bn.

Shipping projects also feature heavily in the plan.

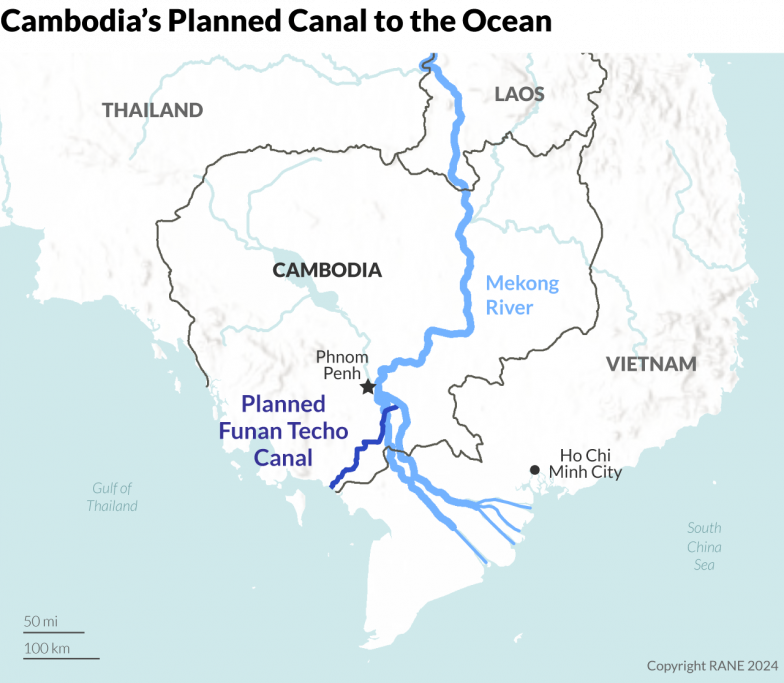

The largest of these is a 180-kilometre-long, 100-metre-wide shipping canal to link the Mekong River system at Phnom Penh directly to the Gulf of Thailand. The $1.7bn channel would bypass the current, less convenient river shipping route that runs the length of the Mekong through Vietnam.

The canal is currently being studied by CRBC for its economic feasibility.

Though little detail has yet come out from that process and no company has signed an official deal to actually build the project, the Cambodian government has announced it will break ground by the end of this year.

The magnitude of the proposal, and the government’s urgency to make it a reality, has caught positive attention from the logistics industry while raising ecological concerns for its potential effects on the transboundary river system.

Poor communication with the public on the details has left residents along the proposed route confused and apprehensive of their ability to stay in their homes.

The canal itself is expected by the Mekong-focused think tank Stimson Center to negatively impact a key floodplain that spans important agricultural regions of Cambodia and Vietnam.

Hong Zhang, a China public policy postdoctoral fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Ash Center, said the momentum of the project could see it through regardless of the concerns.

“If the project has a very strong political backing, I don’t think environmental and social impacts would be in the way or prevent it from happening,” Zhang told Al Jazeera.

Zhang added that Cambodia’s relative political and macroeconomic stability – plus its government’s pro-China stance – has likely afforded it options that other countries would not necessarily get.

“Cambodia continues to be a relatively trouble-free market for Chinese engagement compared to many other countries such as Pakistan, Sri Lanka or even Laos,” she said.

“Even if [the canal] not going to be economically feasible but seems to have good value in terms of its public utility, a lot of externality, this kind of project will be quite legitimate for them to still go back to the old model of borrowing from China with concessional loans, building it and then the government pays back the loan.”

Even if not all the projects in the master plan come to pass, those in the national logistics and transportation industry see a lot to like.

Matthew Owen, the project development executive for the Phnom Penh office of the Singapore-based shipping agency Ben Line Integrated Logistics, said the plan has major potential, but its success will depend on Cambodia’s ability to simultaneously improve the value of its exports.

“I don’t think it’s ‘build it and they will come’, but I think [the government] is ahead of their time,” Owen told Al Jazeera. “Having everything there means they’re going to be able to draw more people in to invest and do business.”

The scramble for large-scale public works is matched with a drive for more private-sector engagement as well, according to Owen.

Owen said the new Cambodian government has been urging international investors from across Asia to get moving on projects initiated before last year’s political handover.

“Everybody’s got an influence, everybody’s got something to gain, and it balances the influence from China,” he said.

“It’s not even a competition, it’s like a pool of countries trying to be Cambodia’s best friend. Cambodia is open to whatever country that’s open to making Cambodia better – if they want to have their own competition of who can build the biggest bridge, go for it.”

Read more here.

Cambodia's Funan Techo Canal Marks a Loss for Vietnam and a Win for China

By Stratfor

Cambodia's new canal project will encourage economic development and connectivity in the country while substantially reducing its dependence on Vietnam, which will stoke national security concerns in Hanoi, while contributing to China's broader geopolitical goal of constructing a global network of friendly ports.

On May 7, Cambodian Deputy Prime Minister Sun Chantol confirmed that construction of the country's Funan Techo canal will begin sometime in 2024, with a target completion date of 2028. The planned canal will span 180 kilometers (around 11 miles), connecting the Phnom Penh Autonomous Port, a river port in the capital, to Kep province on the Gulf of Thailand. Envisioned to be 100 meters wide and up to 5.4 meters deep, it will accommodate vessels weighing up to 3,000 deadweight tons. A Chinese state-owned company, China Road and Bridge Corp., will oversee the development, administration and operation of the $1.7 billion project under Beijing's Belt and Road Initiative, assuming full financial responsibility for its construction and maintenance under a build-operate-transfer model. China Road and Bridge Corp. will then return the canal to Cambodia in 40-50 years once the company has recouped its expenses.

Specifically, the canal will connect the small Mekong River tributary of Prek Teo with Prek Ta Ek and Prek Ta Hing, tributaries of the Bassac River that is itself a major tributary of the Mekong River. The canal will flow through four Cambodian provinces: Kandal, Takeo, Kampot and Kep. The potential environmental impacts of the project remain largely unknown.

Prime Minister Hun Manet announced the initiative at a cabinet meeting in August 2023, his first major infrastructure initiative since taking office earlier that month.

The canal will help develop the industry in Cambodia's interior regions while enabling the country to circumvent Vietnam for trade and gain direct access to global markets, which will encourage foreign investment.

The shipping channel will enable cargo vessels to travel directly from the sea into the interior regions of Cambodia, likely driving growth in inland transportation and industrial development for the Southeast Asian country, which remains a developing economy. The project aims to connect various regions within Cambodia, streamlining costs and time for the transportation of goods, services and people throughout the country. This will also improve Cambodia's transportation networks at large as extra infrastructure, such as roads, bridges and dams, will be constructed along with the canal. The Mekong River, along with its vast network of tributaries, is a major highway network for Cambodian goods and services, and the canal will increase and enhance boat traffic between the coast and the region surrounding the capital Phnom Penh in the country's interior. Moreover, approximately one-third of Cambodia's total imports and exports currently pass through Vietnam as they traverse the Mekong River. This has enabled Hanoi to employ various mechanisms, such as fees and licensing requirements, to collect revenues and maintain substantial influence over the flow of goods in and out of Cambodia. According to the plan, however, the Funan Techo canal is projected to reduce the amount of Cambodian cargo that must pass through Vietnam by 90%. The project will also combine with the Japan-funded Sihanoukville Autonomous Port, a deep-sea container port expected to begin operations in 2026, to allow Cambodia a greater ability to bypass foreign ports and trade directly with markets such as North America and Europe. Overall, the canal will encourage foreign direct investment in Cambodia, a policy priority of the government, by improving both domestic and international connectivity.

The infrastructure blueprint for the canal includes three waterway dams, 11 bridges and over 200 kilometers of sidewalks to accommodate secure navigation and connectivity.

In 1956, South Vietnam restricted access to the Port of Saigon to pressure Cambodian neutrality vis-a-vis North Vietnam. In 1994, Vietnam similarly blocked Cambodian trade along the water route for several months amid territorial tensions over Phu Quoc island. These examples demonstrate Vietnam's powerful leverage over Cambodian trade and, indirectly, over policy.

Cambodia's top imports include pearls and semi-precious or precious stones; mineral fuels and knitted fabrics; mechanical appliances and parts thereof; electrical machinery and parts thereof; and plastics and aluminum. Its top exports include textiles and clothing, both knitted and unknitted; electrical machinery (such as sound recorders and televisions); handbags and other leather products; and footwear, furniture and rubber. The country is also growing as an exporter of solar panels.

Vietnam opposes the project as the canal would inevitably and significantly reduce its leverage over Cambodia, which would result in a loss of revenue and influence for Hanoi, while stoking national security fears of Chinese encirclement and greater Cambodian assertiveness.

While Vietnam has raised alarms that the canal could accommodate Chinese warships, the canal's small dimensions render that highly unlikely. Nonetheless, the canal will accommodate barges, with its 100-meter width sufficient for two-way traffic. This means that small Chinese armed patrol vessels could fit within the waterway. While not posing an outsized national security threat per se, this fuels broader encirclement fears in Vietnam: China to the north, the Chinese-dominated South China Sea to the east, and increasingly Chinese-aligned Laos and Cambodia to the West. However, there are key constraints on China deploying military assets to Cambodia. Hosting foreign troops is forbidden under the Cambodian constitution, and doing so would likely trigger social unrest. It would also reduce the popularity of Cambodia's new prime minister, Hun Manet, as he looks to establish himself after taking over for his father Hun Sen in 2023, who served as prime minister for 38 years. Additionally, Vietnam is worried that Cambodia's diminished trade dependence on Vietnam will make Cambodia increasingly assertive over time, which could threaten to reinvigorate old territorial disputes between the two countries around the Mekong Delta and Phu Quoc island in future decades. Besides national security concerns, Vietnam's opposition to the project also comes from the loss of trade revenues and potential environmental and social impacts, such as the displacement of populations, loss of agricultural land, reduction of wetlands needed for irrigation (thus perpetuating water shortages), and increased salinization of the Mekong Delta.

Vietnam has traditionally regarded Laos and Cambodia within its sphere of influence. The Vietnamese Communist Party historically empowered the two countries' governments in 1975 and 1989, respectively, enabling hegemony over the Indochinese Peninsula until Chinese influence eclipsed its own starting in the 2010s, mostly thanks to economic initiatives, aid, loans and the Belt and Road Initiative that Vietnam cannot match.

China holds over 40% of Cambodia's approximate $10 billion of foreign debt.

Cambodia has not had direct access from the Mekong River to the sea since the early 19th century when Vietnam completed its conquest of the southeasternmost tip of the Mekong Delta. This region, referred to as Kampuchea Krom from the Cambodian perspective, remains a point of contention among Cambodian nationalists who want it back. Indeed, recapturing Kampuchea Krom was the main military objective of Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge's 1978 invasion of Vietnam, and such sentiments could be reinvigorated among the over one million ethnic Khmers living in the so-called Kampuchea Krom region of Vietnam. The region is moreover Vietnam's rice basket and primary source of food, rendering it highly strategically valuable.

Regardless of China's potential military access to the canal, development around the project could also become a strategic threat to Vietnam. Such developments include the potential to link Cambodia to Laos' Chinese-constructed north-south speed rail, which would allow China to more readily access mainland Southeast Asia from its interior in Yunnan province as opposed to almost exclusively relying on its eastern seaboard. Vietnam is likely raising the alarm about Chinese warships despite the dimensions being too small to host them as a diplomatic play to get Washington's attention.

From an environmental point of view, the Mekong Delta is already under extreme stress due to largely unchecked economic development, such as hydroelectric damming upstream, as well as the ongoing impacts of El Nino.

For China, the project could create infrastructure, manufacturing, real estate and tourism investment opportunities, while somewhat contributing to an expanding global network of ports and infrastructure designed to minimise the criticality of the Malacca Strait.

The project will offer economic benefits to China, as a Chinese state-owned company will operate the canal for the next 40-50 years. This will allow China to earn revenues once the canal is completed while also creating greater investment opportunities in Cambodia's interior for Chinese companies — particularly in infrastructure, manufacturing, real estate and tourism — by improving connectivity. It will likewise enhance connectivity with, for example, Cambodia's Sihanoukville Special Economic Zone, a major beneficiary of Chinese Belt and Road Initiative funding. From a broader geopolitical perspective, the canal pairs with other Chinese-funded projects that could create a string of ports from the South China Sea to the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. These include the Ream Naval Base in Cambodia, the proposed Kra landbridge in Thailand, the Kyaukphyu deep sea port in Myanmar, the Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka, the Gwadar Port in Pakistan, and potentially the Khalifa Port in the United Arab Emirates, onto China's only existing foreign naval base at the Port of Doraleh in Djibouti in the Horn of Africa, among others. These are in addition to the hundreds of ports worldwide where China has a controlling stake or substantial investments. For Beijing, this network serves the main strategic purpose of reducing the importance of the Malacca Strait, a critical chokepoint that an adversarial navy could easily blockade in the event of conflict and thus cripple Chinese imports of energy products and foodstuffs, while militarily encircling India. Successfully circumventing the Malacca Strait or minimizing its importance would contribute to securing China's strategic position by eliminating a major vulnerability, which would, in turn, increase the likelihood of future Chinese military action against Taiwan or the Philippines.

The name of the canal, Funan Techo, is itself a reference to ancient ties between China and Cambodia as Funan was the name given to the country by a third-century Chinese explorer.

The Kra landbridge is a new take on an old idea to cut Thailand's Kra Peninsula in half and thus circumvent the Malacca Strait, as well as Singaporean and Malaysian ports. The Thai government is seeking Chinese investment for the project, but China has yet to show official interest in funding it.

Kyaukphyu is a Chinese-funded deep-sea port in Myanmar that may eventually be able to host Chinese warships, similar to Cambodia's Ream Naval Base, but both governments have denied this as a possibility. Construction on the project has yet to break ground.

Hambantota is a deep water port in Sri Lanka where China secured a 99-year lease in 2017.

The Gwadar Port in Pakistan is a key link in China's Belt and Road Initiative and became operational in 2016.

China is also constructing the Khalifa Port in the United Arab Emirates that is suspected to potentially be designed to accommodate Chinese warships as well.

The Port of Doraleh in Djibouti is China's only official overseas military base, which opened in 2017.

According to U.S. intelligence, China now maintains six to eight warships in the Indian Ocean after having no military presence there just two decades ago.

Read more here (paywall).