Could CPEC Become South Asia’s Peace Corridor?

The recent decision to extend CPEC into Afghanistan is a boost to regional cooperation. But geopolitical rivalries cloud hopes.

By Featured contributor Dr. Yasir Masood (The Diplomat)

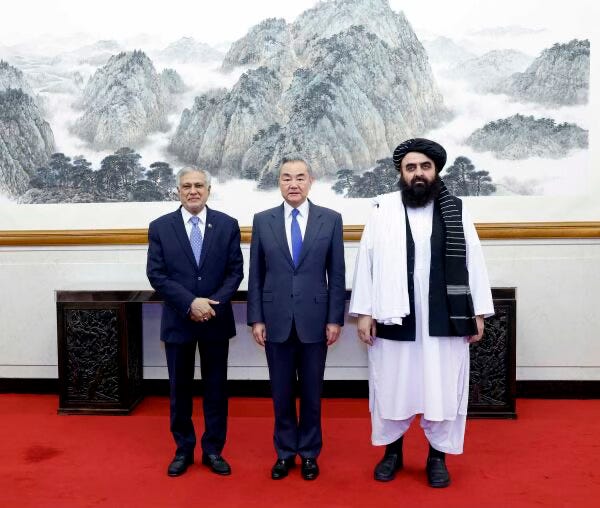

Often hailed by Chinese and Pakistani analysts as a “game-changer,” the multibillion-dollar China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) gained fresh strategic significance recently with Beijing brokering a rapprochement between Pakistan and Afghanistan. At a trilateral meeting in Beijing on May 21, Pakistan’s Foreign Minister Ishaq Dar, his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi and Acting Foreign Minister of Afghanistan Amir Khan Muttaqi “agreed to deepen Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) cooperation and extend the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) to Afghanistan.” The meeting also saw Wang broker the first ambassadorial exchange between Kabul and Islamabad since 2021.

Economic initiatives are embedded in geopolitical realms, with CPEC a blueprint for stability in South Asia. This article examines why the May 2025 breakthrough matters amid hybrid-warfare threats, how peace fuels prosperity, whether CPEC’s Afghan extension could work, and how the corridor could reshape South Asia.

Balochistan, Pakistan’s largest and resource-rich but marginalized province bordering Iran and Afghanistan, hosts Gwadar Port, the gateway to CPEC. As a potential trade hub linking Asia to global markets, it is also a flashpoint for rivalries that fuel regional instability.

Balochistan’s $1 trillion mineral wealth contrasts with the poverty and unemployment of its people, and the poor healthcare and low school enrollment in the province. This has fueled unrest. Decades of inequitable extraction have deepened alienation, pushing some toward separatism. “Our access to the sea has been blocked,” Jamal Peer Bakhsh, a Baloch fisherman from Gwadar, revealed to this writer. Since the port and East Bay Expressway were built, fishermen have to make costly and longer trips into the sea. The government “has failed to create large-scale jobs under CPEC” to protect fishermen’s rights, he said.

A Gwadar-based analyst told this writer that worsening security risks are already disrupting port operations, underscoring the stakes. Meanwhile, the India–Pakistan military faceoff between May 7 and 10 injected urgency into the need for a Pakistan-Afghanistan alignment to counter proxy threats.

It was amid these intensifying security challenges that the breakthrough at Beijing came through.

In an article I wrote in the Express Tribune in 2019, I argued that stronger Pakistan-Afghanistan security ties could unlock CPEC’s potential. Zardasht Shams, a former Afghan diplomat in Pakistan, pointed out that under Presidents Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani, Afghanistan, a historical trade crossroads, supported the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) gas pipeline and CASA-1000, a power transmission project bringing surplus hydroelectricity from Central Asia to South Asia. However, “regional insecurity and instability remained major obstacles.”

While the recent agreement to extend CPEC into Afghanistan is welcome, analysts are calling for caution. CPEC is a bilateral framework between China and Pakistan, and its extension to Afghanistan, “has yet to be realized” under the Third-Party Participation framework, Dr Liaqat Ali Shah, executive director of Pakistan’s Center of Excellence for CPEC, pointed out. Afghanistan’s inclusion can only be sustainable if the region receives investments in infrastructure, industry, and socio-economic development, he said, adding that the country can’t be used merely as a land bridge connecting South Asia with Central Asia.

“CPEC is currently restrained within a bilateral framework,” Prof Ye Hailin, president of the Chinese Society of South Asia Studies in Beijing, said. “With Afghanistan’s situation improving,” the framework should include Afghanistan and expand into a regional cooperation arrangement.”

The Afghan perspective underscores the stakes. The decision to extend CPEC to Afghanistan “is a very big and important step for Afghanistan, Pakistan, and China,” former Kabul Governor Ahmad Ullah Alizai said. However, he warned that “if this starts now, there will be a lot of security and political problems.”

Despite these hurdles, regional connectivity is gaining traction. Gwadar links Central Asia to warm waters, but its potential, notes Islamabad strategist Hassan Daud Butt, “hinges on Afghanistan’s inclusion in the Belt and Road.” China is emerging as “not just the center of gravity, but the center of certainty,” he said. Additionally, Operation Azm-i-Istehkam(Resolve for Stability), launched in June 2024 by the Pakistan military against the TTP, secured CPEC routes by mid-2025 despite lingering mistrust between security forces and local populations.

However, the promising progress faces significant obstacles. In my observation over the past decade covering CPEC and the Belt and Road, two main sabotage tactics have consistently emerged: the deliberate spread of disinformation to create uncertainty around CPEC’s benefits, and the use of terror networks and non-state actors in Balochistan and along the Afghan-Pakistan border to fuel instability and hinder development. This narrative is detailed in my earlier article “The CPEC Narrative.” The aim is clear: to fuel unrest and keep CPEC in limbo.

Among those saboteurs, India is the most active state sponsor. India’s proxy warfare in Balochistan, exposed by the 2016 capture of spy Kulbhushan Jadhav, fuels militant groups like the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA), a separatist militant group and globally listed terrorist outfit, through arms, disinformation, and sabotage of Chinese infrastructure, evident in attacks such as the Jaffar Express ambush. Guided by the Ajit Doval Doctrine, India’s blueprint uses consulates near Pakistan’s border to destabilize CPEC, viewing it as a regional threat. By arming BLA factions and targeting Chinese projects, New Delhi aims to dismantle Pakistan’s economy and negatively impact the Baloch conflict, as reflected in Indian narratives through typical media hybrid-warfare tactics. Chinese journalists, too, allege that India is supporting proxies in Balochistan to disrupt CPEC, another cog in the “China containment policy.”

Proxy wars have worsened Pakistan’s security. According to the Global Terrorism Index 2025, attacks rose 45 percent to 1,099 in 2024, making Pakistan the second most affected by terrorism in the world. BLA and the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) carried out over 986 attacks, killing nearly 946 people. BLA recruits youth online, spreading anti-CPEC propaganda. TTP uses Afghan safe havens. The attack on Jaffar Express at the Bolan Pass in March, which killed 21 people, exposed the role of India’s intelligence agency, RAW, via Afghanistan. BLA attacks rose from 116 to 504 between 2023 and 2024, causing 388 deaths, while attacks by TTP increased from 293 to 482 and resulted in 558 fatalities in the same period. As reported by South Asian Terrorism Portal (SATP), attacks rose from 116 in 2023 to 504 in 2024, causing 388 deaths; meanwhile, TTP attacks increased from 293 to 482 over the same period, resulting in 558 fatalities.

A Chinese media outlet reported in April 2025 that Pakistani security forces killed 50 militants with “Made in India” weapons.

External pressures worsen internal threats. Since 2001, India has invested over $3 billion in Afghanistan, presented as aid but securing New Delhi a regional foothold, and aimed at exploiting Pakistan’s internal fissures. Islamabad fears Indian influence in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, fueling its sense of strategic encirclement and adding to domestic instability, which India denies.

CPEC now shapes regional strategy. The May 2025 breakthrough has enabled realignment, linking peace to prosperity and expanding CPEC into Afghanistan, offering Pakistan a chance to offset India’s undermining efforts.

Yet CPEC faces targeted violence, hybrid warfare, local frustrations, and external geopolitical interference. Success requires tangible progress: moving beyond statements, especially in Balochistan, securing routes, investing in communities, and making local stakeholders. Only then can CPEC transcend headlines and deliver durable stability and cooperation in South Asia.

NB: Dr. Yasir Masood is a Beijing-based Pakistani political and security analyst specializing in BRI, CPEC, South Asian and Indo-Pacific geopolitics, China-U.S. relations, and Chinese foreign policy. He holds a PhD in International Relations from UIBE, Beijing, with research on the Balochistan conflict and regional stability. A former Media and Publications Director at the Centre of Excellence for CPEC, he has conducted fieldwork in Gwadar and regularly contributes to international media and think tanks.